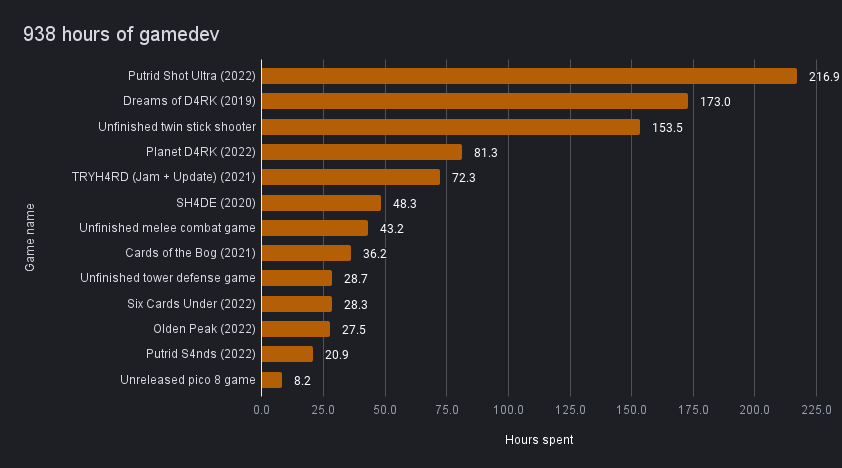

Over the past three and a half years, I’ve spent 938 hours making different games. The games ranged from short projects taking only 20-30 hours to much longer projects taking upwards of 200 hours with many unfinished projects scattered in between.

While some went unfinished, most of the projects ended up shipping in one way or another. In tracking my gamedev time, I learned how long it takes me to “make a thing”, what types of projects cause me to burn out, and how time tracking affects the way I work in general.

My game "Olden Peak" took 27.5 hours to make

Time Tracking as a Productivity Hack

It’s a pretty common productivity hack to use a timer to help you maintain focus. Starting a timer forces me to focus at the start of a task, and the ticking of the timer increases the guilt I feel when I get distracted.

I started tracking time to find more time in the day for my many hobbies and find where I was wasting time. Tracking everything I did ended up being a huge pain, so nowadays I only record how much time I spend on hobbies.

Since then, my goal became to better-understand how long it takes me to actually make things, so I could better-scope my projects around a tight schedule. I ended up learning a lot about how long it takes me to create a certain amount of gameplay, and how that time scales with respect to a game’s scope. I also learned that tracking time can cause me to optimize the time I spend in interesting ways, both good and bad.

Logistics

I use an app called aTracker (disclaimer: I am not sponsored by this app). It has a free version that I used for the first year with good success but I’ve since upgraded to the paid version to avoid the ads. For every new gamedev project I start, I create a new “task” on the app.

Whenever I’m about to work on the project, I tap the project to start the timer and stop the timer when I stop working. When I’m finshed with a project, I archive the task on the app. The app keeps track of the total time spent on each task, so with the above workflow I can measure how long it takes me to “make a thing”.'

![]()

Here's the UI for showing every game I've tracked. I track time for a variety of personal tasks as well which I've crossed out for privacy reasons

How long does it take me to make a thing?

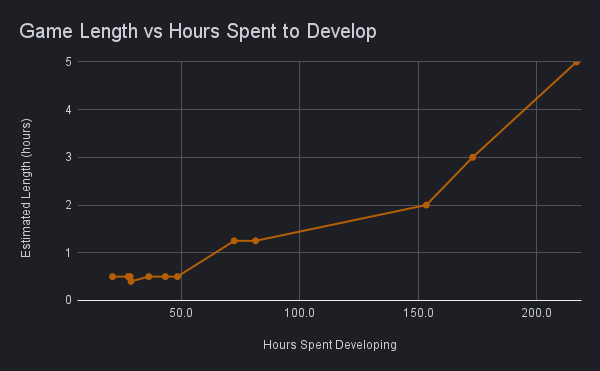

In the near 1000 hours I’ve spent on gamedev in the past 3.5 years, I’ve worked on around 13 games, ranging from tiny 1-2 week projects (~20-30 hours) to multi-month commercial ordeals. Since my goal was to better understand how long each “unit of content” takes for me to create, let’s look at game length VS hours spent developing:

Estimated Length is the time needed to almost 100% the game

No surprises here. The longer I spend on a game, the more content I can create. There aren’t that many samples in the 100-200 hour range, so the graph could be a bit misleading there. However, I do think that the more time you invest in a game, the better the “rate of return” on content is, and I’ll talk about that in the next sections.

You’ll also notice that the games I make tend to fall into one of three buckets:

- Short projects (20-50 hours)

- Medium projects (70-90 hours)

- Long projects (150-200 hours)

Short Projects (20-50 hours)

These were usually PICO-8 games. The PICO-8 engine’s restrictions force me to ship games roughly at the 30 hour mark unless I’m working overtime on music and story. PICO-8 prevents you from having more than 8192 symbols in your code (which translates to around 2000 lines of lua code), which usually takes me around 30 hours to write.

My game "SH4DE" took a bit longer (48 hours) to make as I was still learning pico-8

"Cards of the Bog" took only 36 hours to make

These games probably had the best “fulfillment-to-effort” ratio. I’d spend between 1-3 weeks on a simple idea, expand on it as much as I could in that time, and then ship a game. Each of these games got thousands of plays on itch.io, despite only taking a few weeks to make. I rarely got sick of working on these games due to their short development cycle.

And if I ever got sick of one of these games, I felt comfortable shelving the project indefinitely due to the lack of a sunk cost.

The only problem with this category of games is that their “content-to-effort” ratio is lower than other categories. This is because it often takes me at least 5-10 hours to set up the core systems of a game.

Given that this initial startup cost gets paid no matter the length of game I’m working on, spending only an additional 10-20 hours actually creating content can feel a little wasteful.

Medium Projects (70-90 hours)

These projects were more meaty games with multiple levels, fully fleshed out stories, and deeper mechanics. I only made two of these games over the last few years.

"Planet D4RK" took 81 hours to make and received over 40000 plays on ArmorGames

The full version of "TRYH4RD" took 72 hours to make and received over 40000 plays on ArmorGames

I think this is my sweet spot for the “effort-to-content” ratio. I still pay the initial “game systems dev” startup cost, but I’m able to spend more time squeezing every drop of content out of the idea.

For example, the original jam version of TRYH4RD only took and featured only 3 bosses and took ~40 hours to make. However, feeling that there was more to explore with the mechanics, I spent another 30 hours adding new remixes of the bosses and attack patterns on the existing systems.

Since I’d already written the core combat, I could spend these 30 hours really fleshing out crazy attack patterns that fans really loved.

Long Projects (150+ hours)

For me, these are the real soulsuckers of hobbyist gamedev. The ones I wish I’d never started; The ones I wanted to quit if not for their sunk costs; The ones where simply shipping the game feels like an accomplishment.

I made "Jingnon's Ascent" before I started time tracking. It took well over a year to finish

I spent over a year on "Dreams of D4RK". I started time tracking in the middle of development and never finished the game

I spent 150 hours on this unfinished twinstick shooter, implementing roguelike mechanics, branching dialogue trees, and cutscenes. I gave up right before finishing the final boss

Quite a few of my games in this category are unfinished. I only finished the demo for Dreams of D4RK, and my twinstick shooter never saw the light of day. Jignon’s Ascent only shipped because I realized I would never finish unless I gave myself a hard deadline and aggressively descoped.

I think these projects are the most dangerous to me as a hobbyist dev. I can really only spend around 1 hour per day on gamedev, so a 200 hour project can easily take me 6 months to a year to complete. This is a long time to spend on a single game, especially as one person. The allure of picking up a new technology or running with a new game idea is ever-present and tantalizingly strong when working on one of these projects.

That said, I’m happy that my first commercial project was finished in only around 200 hours. That game’s sold around 530 units so far, and continues to sell (albeit very slowly).

Time investment and burnout

Unsurprisingly, low investment projects tend to be a lot less stressful. Shipping five 20 hour projects doesn’t burn me out at all, while shipping (or worse, failing to ship) one 100 hour project destroys my motivation for months. I feel very vulnerable to the sunk cost fallacy, so I’d been avoiding longer projects for a while up until I made my commercial game. That said, I think I tend to push myself the most when it comes to longer, more feature-rich projects.

Optimizing for “number of hours”

When I start tracking something as a number, I naturally start to optimize for it.

When I started tracking gamedev time, I subconsiously started trying to optimize that number. This ended up being both good and bad for me.

The good: Focus and efficiency

Tracking my gamedev time has forced me to focus 100% of my energy on gamedev when the timer starts. I enter a “flow state” much faster now, and can make tons of progress in the 1-2 hours that I spend on it at a time.

I no longer listen to youtube videos or podcasts in the background of gamedev. I focus all my energy on the current task and I feel really productive when I’m working on games.

The bad: Cutting corners

Since I’m trying to optimize the “time spent” number, I found myself cutting corners quite often, especially during my most recent commercial project. I reached a point where I realized making “good art” for the game, or truly improving my art skills, would have taken too much time. So I simply made bad art for the game and covered it up with VFX and juice.

The game has decent juice, but I think I could have done better art-wise

I caught myself doing the same on my current project. I want to improve my art, but started off half-assing the art with the intention of maximizing my “content-per-hour” ratio so I could make the game faster. Since then I’ve tried taking things slower.

Conclusion

I still track the time I spend on gamedev because I like knowing how long it takes me to make a game. If I know that I’ll have a free schedule for 2 weeks, I can “budget” time for a quick pico 8 game because I know that it’ll only take me 20-30 hours of work.

This has made it really easy to confidently explore weird ideas knowing that I won’t get caught in some multi-month-long sunk cost. This is also why I shipped so many games in 2022.

I’m also able to catch myself before diving into an insanely deep project because I can look at my time spent, compare it to the time spent for other projects, and make a well-educated guess on how much longer it will take to finish.

However, I’ve been trying to catch myself “optimizing”, to make sure I’m not intentionally creating subpar content just for the sake of maximizing my “content-per-hour” ratio. It’s a lot harder to commit to learning a new skill while making a game if you’re watching a timer tick up with every minute you spend fumbling around with this new skill. For that reason, I’ve been trying to be more detached with my time tracking.

All that said, I highly recommend tracking the time you spend on projects. Not for efficiency or productivity, but just to help you understand how long it takes to make something you like. If nothing else, it feels really good to look back at how much time you’ve spent doing something you love.

————————————-

Woof, this article ended up being way longer than I had intended. I was originally going to include data on the “number of players VS hours spent developing”, but it got way too long; I may return to this topic later. If you want to be notified when I make posts like this, consider signing up for my mailing list.